Many business leaders claim to seek disruptive technology launching them beyond the grasp of their competitors.

Do they really want disruption?

True disruptive advancements are inherently discontinuous.

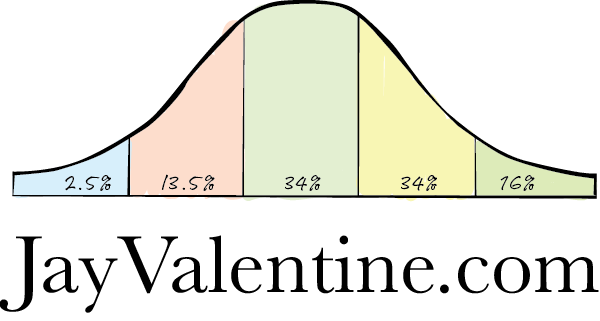

The Disruption Paradox = business leaders attempting discontinuous advancement with incremental tools. Incremental and disruptive are opposites.

Let’s take the most compelling example today.

Major businesses claim they will achieve digital transformation moving to the cloud. They hire armies of consultants to either “lift-and-shift” current apps or rewrite apps with current technology.

Executives are realizing moving apps to the cloud is not transformational. It is just someone else’s computer. The apps run the same, cost about as much, maybe are a bit easier to set up. No disruption there.

That is the Disruption Paradox. Current technology and toolsets cannot be disruptive. As Albert Einstein noted, one cannot solve a problem with the same tools that created it in the first place.

Today over 67 percent of a typical firm’s IT budget goes to IBM, Oracle, SAP, VMware, security vendors, body shops and scores of established software vendors. These vendors are the “conventional wisdom” of the market. They do things as they always have been done – for 40 years.

They are the status quo because they created it.

Oracle in the cloud is Oracle with all the nasty licensing, terrible data redundancy, complicated app development, expensive skills – just in the cloud.

IT management lives within these vendor ecosystems – and constraints. They learn about new technology seeing status quo firms’ incremental changes. They attend raucous user group sessions to hear about Version 25.2.3 of some almost obsolete technology on which they likely spend millions of dollars a year.

The second leg of the Disruption Paradox is modern companies are so locked into current technology there is neither the time nor interest to try a novel technology leading to massively different outcomes.

Executives, particularly tech execs, who have done IT a certain way for literally a generation are seldom open to a technology that will launch their company into bountiful new markets.

A business unit head can see the novel technology, opening new markets, as a glass half full. The IT exec sees the same equation, from the vantage of “we do not have expertise in this new technology” like a glass half empty. The Disruption Paradox just got more complicated.

It gets worse.

There is a mindset one needs to run a conventional IT organization or even the business unit itself. There is also a self-selection process that governs who sits atop.

The mindset and selection process frequently deliver occupants who are not risk-takers; they are managers who make the trains run on time. That is not the mindset of the innovator, it is that of the bureaucrat. Bureaucrats do not innovate; they move incrementally if they move at all.

Much of the early success of the cloud market was because companies needed to show they were moving to transformation, agility and disruptive change. The cloud gave them something special: transformation theater.

The cloud allowed executives to “do something” with current technology. It was not scary, not innovative and certainly not disruptive. The cloud was just their infrastructure somewhere else.

The good news is they keep working, they receive a budget and they report progress. The bad news is beginning to trickle in: in the cloud, apps run just the same, cost the same as in the data center. Nothing changes.

While nobody loses, worse, nobody wins. Except for Microsoft and Amazon.

The result of the Disruption Paradox is that to find the future, open those new markets with game-changing technology, one must be either a natural innovator or under such pressure that risk-taking has no downside.

Those two groups are found not in the market leader. They are found in the also-rans who have ambition and hopes and are willing to roll the dice.